When I come across a bunch of raw water in the backcountry, what do I do? Sometimes I swim in it, sometimes I desperately try to avoid it in the hopes of staying dry, and sometimes I drink it. When I drink it, do I keep it raw? Very rarely. During my Appalachian Trail (AT) and Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) thru-hikes, the most popular approaches when it came to drinking raw water were to:

- Filter it: Sawyer Squeeze Mini (0.1 Micron Filter, $20/2oz)

- Chemically purify it: Aqua Mira ($15/2oz) or bleach (2 drops/liter)

- Purify it with Ultraviolet (UV) light: Steripen ($69.95/2.6 oz)

- Choose wisely and take your chances: select high-flow springs whenever possible; otherwise select lower flow springs or small spring- or glacier-fed streams

- Boil the piss out of it

When I read the title of the link that started showing up in my feeds yesterday, “Actually Backpackers You Don’t Need to Filter Your Stream Water” my initial thought was, #notwrong. Unless my stream water is chunky or green I don’t usually don’t filter it, I purify it. I was surprised when I opened the article and realized that the title wasn’t a bait-and-switch about other water treatment options, the article was really suggesting that treating backcountry water sources for contamination was unnecessary:

“Treating backcountry water sources for contamination is a fundamental tenet of outdoor recreation education, ignored at the peril of contracting giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, or worse. In this case, however, popular opinion is wrong: The idea that most wilderness water sources are inherently unsafe is baseless dogma, unsupported by any epidemiological evidence… research to date has failed to demonstrate any significant link between wilderness water consumption and infection with these threats”

It is certainly true that the popular opinion in the backpacking community is that you should treat backcountry water sources for contamination, is it also true that there is no link between untreated backcountry water sources and giardia or other water-borne illnesses? (Spoiler Alert: the CDC released epidemiological evidence in 2015 and 2017 linking giardia outbreaks to a backcountry water sources). I settled in and made myself comfortable, curious to see whether the Slate was going to impress me with their SCIENCE or or with their SPIN. Ok, are you ready for it?

I started by looking up the cited 1993 study, “Cyst acquisition rate for Giardia lamblia in backcountry travelers to Desolation Wilderness, Lake Tahoe.” (Zell et al, 1993):

- 5.7% (2/35) of the backcountry travelers (1988-1990) acquired giardia cysts during their backcountry trips but remained asymptomatic

- 16.7% (6/36?) of the backcountry travelers (1988-1990) experienced acute gastrointestinal illness (AGI), but did not show giardia in their stool. However, 1 of the 6 was diagnosed with giardia and treated with flagyl.

- ≤25 giardia cysts per 100 gallon water sample (sampled at 2 gallons/minute) were found in the one trailside creek (Meek’s Creek) they evaluated in 1988

- NOTE: According to the EPA, “As few as ten human-source Giardia cysts produced infection in a clinical study of male volunteers.”

In summary, they showed that ~6% of backpackers acquired giardia in the backcountry, ~17% of the backpackers suffered from some sort of gastrointestinal illness, and they found giardia cysts in the one wilderness creek that they looked at. Given that their data was collected roughly 30 years ago, I was actually surprised that they found as much giardia as they did. Since the number of humans are one of the largest sources of giardia contamination, and the number of humans heading into the backcountry (and pooping in it) has been increasing over the last 30 years, I’d expect the amount of Giardia to be even higher now. For example, in 1988 there were 31 thru-hikers that hiked through the Desolation Wilderness on their way to completing their Pacific Crest Trail thru-hikes, whereas 717 backpacker passed through there on the way to successfully completing their thrus in 2016. I think it’s also important to note that the quotes in the Slate.com article about wilderness are all referring back to this one wilderness, which is wilderness as defined by the Wilderness Act, and not generic wilderness areas.

Although I enjoyed reading the 1993 paper, it didn’t convince me that backpackers in 2018 should drink raw, untreated water from streams. I’d hiked through the Desolation Wilderness during my 2014 PCT thru-hike and opted not to drink the raw stream water then, and the evidence they’d presented so far wouldn’t lead me to make a different decision now. My general rule is to always filter, purify, or otherwise treat my water if there’s any chance that animals have been pooping, bathing, or swimming in it (especially if those animals are humans, beavers, or domesticated animals). Even though the glacially-fed mountain lakes and streams of the High Sierra were some of the most beautiful waters I’ve seen, I still always treated my stream water before drinking it because there was still a chance that someone or something higher upstream had been pooping in it. (As an aside, the backcountry contaminant I was most worried about as I hiked into the High Sierras was uranium, which is found in almost all of the groundwater of the high sierras; I shared my thoughts about the PCT water situation at the time in my trail blog: PCT Days 40-42).

The next paper the slate article cited, the 1995 survey of health departments, was based on data more than 25 years old that found that 10.5% (2/19) of reported giardia outbreaks from contaminated drinking water were reported by campers/backpackers. The final scientific paper the slate article mentions was a meta-analysis published by Welch in 2000, which initially looked promising, but on further investigation, the only data that they included (met their inclusion criteria) about backcountry scenarios was from 1977. I wasn’t feeling wowed by the Science in the slate article at that point, so I decided that instead of jumping into the way-back machine and delving into data collected from before I was born, I would see if there was a more recent discussion about giardia in the backcountry in the scientific literature.

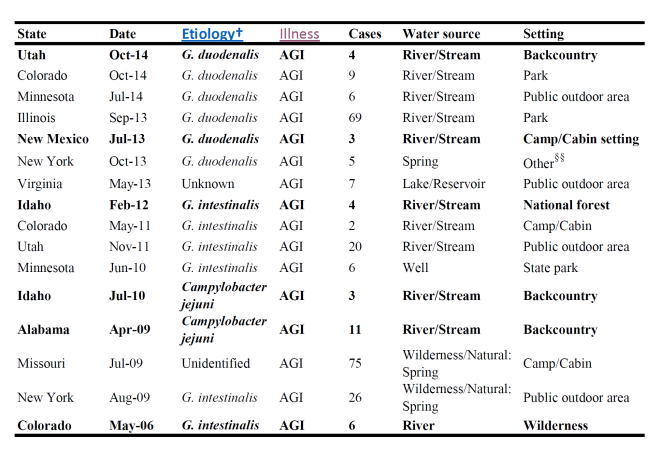

- CDC 2017: “Six outbreaks of giardiasis caused by ingestion of water from a river, stream, or spring.” (The backcountry is specifically implicated in Table 2), “Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated With Environmental and Undetermined Exposures to Water — United States, 2013–2014”

- CDC 2015: “Three Giardia intestinalis outbreaks occurred, following drinking of untreated water directly from rivers or streams in outdoor settings.” “Outbreaks Associated With Environmental and Undetermined Water Exposures — United States, 2011–2012”

It didn’t take me long to find it. In November 2017 the CDC released information about waterborne disease outbreaks collected during 2013 and 2014 (the years I did my thru-hikes of the AT, and PCT, respectively), which included outbreaks of giardia in backcountry settings and in national forests that were caused by drinking water from a river, stream, or spring. The 2011 and 2012 data also specifically cites giardia outbreaks that occurred from drinking untreated water directly from streams or rivers in outdoor settings. These giardia outbreaks are only the ones that met the CDC’s criteria and don’t include individual cases that may be scattered along the trail (e.g. my 2013 case of Giardia from the 100 mile Wilderness on the AT isn’t included in the CDC statistics).

Update: 2/5/2018. Selected outbreaks caused by backcountry, wilderness, and other outdoor water sources (river, stream, and/or spring) reported by the CDC. AGI: acute gastrointestinal illness, G.duodenalis: giardia duodenalis, G. intestinalis: giardia intestinalis

In addition to the epidemiological data from the CDC, I also found a meta-analysis looking at data in both the US and Canada from 1971 to 2014 (published in 2015) that stated that “Half of the outbreaks… were located in camps/ campgrounds/ cabins/ parks“, and found that 35% (101) of outbreaks were from camp/ campgrounds.

After spending some time wading through the science (additional links available at the end of this post), I wasn’t feeling tempted to save money and lighten my pack by choosing to drink lots of raw, completely untreated stream water. The perspective shared in, “Actually Backpackers You Don’t Need to Filter Your Stream Water”, seems outdated in terms of the science, the technology, and the culture. Sure, back in the 1980’s and 1990’s the dogma in the outdoor community was that the average hiker needed to carry a $99.95 water filter that weighed almost a pound, but in 2018 most folks (myself included) are more likely to suggest lighter (2-3 oz) and less expensive (<$25) water treatment solutions. The scientific data from Slate’s sources show that giardia is present in at least some backcountry water sources, and the epidemiological data I found links giardia to at least some backcountry and wilderness water sources. Overall, the data suggests that there is some risk associated with drinking raw, untreated water. Whether or not you feel it is an acceptable risk is a completely different question.

I almost always filter or treat raw water from backcountry water sources. Although often my options when it come to backcountry water sources are limited, if I have a choice I have a preference. My personal preferences (along with the treatment options I use) are:

- Springwater coming out of the side of a mountain (raw or purified)

- Bubbling spring with a high flow rate (raw or purified)

- Piped springs (purified or raw)

- Beautifully clear waterfalls (purified or filtered)

- Streams (purified or filtered)

- Rivers or Glacial Lakes (purified or filtered)

- Cisterns (purified and/or filtered)

- Lakewater and pond water (purified & filtered)

- Chunky and/or green water (pre-filtered, filtered &/or purified)

- Cow pasture water (purified & filtered & boiled)

Over the years I’ve consumed thousands of liters of water from backcountry water sources in the US, and I’ve only gotten giardia once…

I got giardia from a pristine looking stream near a shelter in the 100 Mile Wilderness in Maine on Day 147 of my 2013 Appalachian Trail thru-hike. I was really shaken up from having a tree almost fall on me, and distractedly gulped down a whole bunch of my water 20 seconds after adding Aquamira to it. I realized my error almost immediately, but the water was clear and the stream was pretty, so I was cautiously optimistic. About 10 minutes later the trail led me to the beaver pond that my stream had flowed from. Doh! I summitted Katahdin, finished my AT thru-hike, and didn’t think any more about it until a couple weeks later when a gastroenterologist suggested that town food wasn’t my problem, giardia was.

Once was more than enough for me. For me, $20 and 2 oz seems like a pretty low cost (both in terms of $$ and weigh) to decrease the odds of having to go through that again.

7 Questions to Ask Before Drinking Raw Water

As we do more and more research on the importance of microbiomes in human health, I expect that conversations about raw water will grow. Over time our interactions with backcountry water sources may evolve, and we may develop better tools to guide our interactions with raw water. In the meantime, here are 7 questions I ask myself, and would encourage others to ask themselves, before drinking untreated raw water from backcountry sources (or any other source really):

- Are you in a long-term monogamous relationship with your raw water source?

- Does you raw water get routine testing for water-borne infections (WBIs)?

- Does it have unprotected contact with the bodily fluids (or solids) of other people? strangers? beavers? livestock?

- Does it have a history of unprotected contact with bodily fluids or other substances that could negatively impact your health?

- Sure, it’s beautiful, but how much do you really know about it?

- Who and/or what was your raw water with before it was with you?

- Do you really know enough about its history to want to be fluid-bonded with it?

In general, I would strongly advise hikers and backpackers to treat the water they take from streams before drinking it. If you do decide to drink raw backcountry stream water, you might want to consider abstaining during periods of heavy rainfall when the risk of drinking raw stream water is higher than usual because waterborne contaminant levels in streams (even in the high sierra) are highest after large amounts of rainfall.

NOTE: Although I know a few people that got giardia on the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail, I know a lot more people that got Norovirus or Lyme disease (see links below) on their Appalachian Trail thru-hikes.

Related Posts I’ve Written:

- Backpacking Science and Privilege: Water

- 5 Ways to Keep Mosquitoes and Ticks from Bugging You! (Gear Guide+)

- Ticks & Lyme Disease

- Norovirus on the trail: The Hiker Plague (AT Days 28-30)

Links to Additional Information About Giardia:

- Fact Sheets:

- Giardia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Giardia and Dogs

- Abstract talking about giardia and dogs in the US: “Prevalence and risk factors for Giardia spp. infection in a large national sample of pet dogs visiting veterinary hospitals in the United States (2003-2009).” Vet Parasitol. 2013 Jul 1;195(1-2):35-41. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.049. Epub 2013 Jan 3.

- Abstract talking about dogs, humans, and giardia: Temporal patterns of human and canine Giardia infection in the United States: 2003-2009. Prev Vet Med. 2014 Feb 1;113(2):249-56. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.11.006. Epub 2013 Nov 20.

- Giardia and Beavers

- Waterborne Disease Outbreaks in the US and Canada

- Specific References for Backpackers in the Sierra Nevada (Added: 2/5/2018):

- An Assessment of Diarrhea Among Long-Distance Backpackers in the Sierra Nevada. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Mar;28(1):4-9.

- Effects of Backpacker Use, Pack Stock Trail Use, and Pack Stock Grazing on Water-Quality Indicators, Including Nutrients, E. coli, Hormones, and Pharmaceuticals, in Yosemite National Park, USA. Environ Manage. 2017 Sep;60(3):526-543. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0899-z. Epub 2017 Jun 8.

- Backpacking in Yosemite and Kings Canyon National Parks and neighboring wilderness areas: how safe is the water to drink? J Travel Med. 2008 Jul-Aug;15(4):209-15. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00201.x.

- Risk factors for coliform bacteria in backcountry lakes and streams in the Sierra Nevada mountains: a 5-year study. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008 Summer;19(2):82-90. doi: 10.1580/07-WEME-OR-1511.1.

Solid advice. What was Slate thinking?

Squarely in the “treat it” camp.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always helpful and always well written Thanks

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a wonderful article. I always filter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Come on! A little ameobic dysentery builds character.

In all seriousness, except for a few exceptions in the Sierra, i always filter my water. When I was a kid back in the 80s I used to drink straight from streams and springs. Then my uncle got Giardasis, and that changed how my uncle and I viewed those mountain streams.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for including links to the relevant research! I’m definitely guilty of skipping the aquamira when drinking from those crystal clear streams… I definitely agree with your conclusion, “Overall the data suggests that there is some risk associated with drinking raw, untreated water. Whether or not you feel it is an acceptable risk is a completely different question.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Where do you do most of your backpacking? There seems to be a lot of regional variation in how people relate to the risk, especially when it comes to drinking from streams.

LikeLike

Never mind the odds, always pay attention to the risk.

Very well-documented article. Thanks.

LikeLike

Outstanding article. That’s how to do research and that’s how to think. Here’s some additional points: in the Zell study those people got sick after a SINGLE TRIP. Also one of the most maddening mistakes in the medical literature is the “as little as 10 cysts” infectious dose for giardiasis. Actually it’s as little as one cyst (2% chance) as per the Rose study. And the Wright study, which only looked at lab confirmed giardiasis cases found: “drinking untreated mountain water is an important cause of endemic infection” I cite those studies here: http://bucktrack.com/water.html

LikeLike

Yeah, prompted by these discussions, I’ve been doing a more in depth review of the literature and finding all sorts of fun facts. I say the Rose paper, but haven’t delved into it yet. I’ll check out the stuff you have up.

LikeLike